A Practitioner’s Response to the National Model Design Code

It can often feel like we are engaged in a long struggle against the spread of new development that has been packaged and branded into a facsimile of the places that people supposedly want to live.

Is The National Model Design Code (the NMDC) part of a genuine attempt for change, or is it yet more rhetoric being used to pacify legitimate concerns over the quality of new development.

It should be stressed that the NMDC is undergoing test piloting and is expected to evolve further before being finalised.

The extensive use of visuals in the NMDC and accompanying Guidance Notes for Design Codes (2021), helps maintain interest and brings the guidance to life with easy to interpret graphical forms. Indeed the balance between text and visuals sets a good barometer for local planning authorities (LPAs) to follow in their own codes.

The notion of analysing large areas (settlements) to be covered by a design code and dividing this up into a series of ‘Area Types’ (or character areas) is also well-received. More on this to follow later.

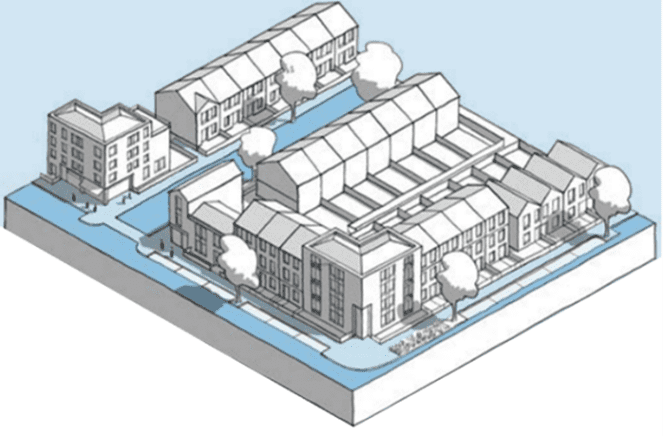

Another strong suit is how the NMDC provides a template for producing design codes that encompass the full range of spatial scales: Strategic-scale design approaches such as movement and landscape; to developing appropriate urban form at the scale of neighbourhoods; and finally coding elements to do with the architectural and engineering details of place.

Where am I? Pushing Back Against the Spread of Sameness

So far so good. However, the NMDC alone will not arrest the current trend of homogenised new housing developments. It is however a step in the right direction. In the era of off-the-shelf design many residential developers will propose their preferred suburban development models regardless of context.

This means many local authorities come under pressure to accept the same suburban-type development models regardless of where it is proposed. This is especially true where a site falls outside of a conservation area, or is not within an area covered by a specific design policy such as an Area Action Plan.

That is why the advent of ‘Area Type’ codes is seen in positive terms because in theory they are about making sure new development forms a logical and positive response to the attributes of the area.

It may appear a minor and innocuous thing but by talking about ‘area type’ rather than ‘character area’ the NMDC is addressing decades of misinterpretation of the term character. Character has nothing, absolutely nothing, to do with replication. Yet the term character is too often conflated with heritage designation. In the wrong hands this has resulted in new development being designed as replicas of designated heritage assets (such as areas of Victorian or Georgian architecture) as developers go in search of a notional form of character supposedly found in way a building looks. In taking about ‘area types’ future design codes can focus on understanding what is really meant by character: the sum of attributes found in a given place. These attributes could be to do with landscape, topography, views, movement, grain, three dimensional form, diversity of uses, local materials, public spaces, street network and hierarchy to name a few. The more we have local design codes that are able to focus on this, the stronger our resistance to the hegemony of sameness.

Elephant in the Code

A criticism of the NMDC is that it has shied away from addressing the conflict that exists between the urbanism prescribed in URBED’s excellent illustrations, and the application of normative design standards that often lead to the type of car-dominated suburban developments we’re all sadly too familiar with.

As evidenced by A Housing Design Audit for England (2020) by Place Alliance, once local highway adoptions standards are applied, and arbitrary parking standards taken into account, the urbanism illustrated within the pages of the NMDC is almost impossible to deliver. This raises the question of whether the NMDC may have over promised, and is at risk of flattering to deceive.

Another more positive perspective is that there is optimism to be had in the belief that the NMDC and Manual For Streets 3 (MfS3) will work together. With a glass half-full the NMDC can be seen as a frontrunner of better things to come. MfS3 is expected later in 2021 and will need to be underscored by technical guidance that allows highway adoption standards to be applied with greater flexibility in a response to context.

How will Design Codes be Resourced?

Design resources within local authorities remains patchy. Recently I helped set up the Local Government Officers’ Design Group and a poll of members on design resources, whilst anecdotal, suggests many are not currently resourced to produce such illustrative local design codes (time, budgets, skills, IT software and staffing all prohibitive).

This has been confirmed recently by another Place Alliance survey and report The Design Deficit published in July 2021. It finds that two fifths of LPAs still have no access to urban design advice; almost two thirds no landscape advice; and three quarters no architectural advice. The true extent of the deficit is likely to be hidden by the sharing of posts, use of temporary staff and coverage by non-design specialists. Some LPAs may not have the capacity and resources to produce codes in-house. Yet if they’re to become effective tools design codes must not be imposed upon LPAs. To overcome this issue of resourcing local codes could be developed in partnerships between local authorities, developers and landowners. This approach would likely necessitate some form of independent arbiter to appraise the process and codes themselves – Design Review services, or similar. The new Office For Place may well need to be proactive in this respect.

New Approaches to Stakeholder Engagement

Stakeholder consultation and engagement during the production of local codes will require a balance of traditional and new digital techniques appropriate to the type and scale of new development envisaged. New digital approaches such a PlaceChangers and other online tools used for engagement and measuring support, must now become the foremost method of engagement.

Currently the statutory requirements surrounding public consultation can make it laborious and inefficient – with significant resources taken up in recording each and every response to a consultation, and providing written responses to each.

The emphasis should be on the quality of engagement and the impact it has had rather than the transcript of what was said by whom. This itself will need resourcing and local authority staff will require training to be competent in the use of digital techniques and applications, not to mention being design literate themselves.

With the publication and further testing taking place of the NMDC it is encouraging to see greater emphasis being placed on design quality. New investment and a redistribution of design resources is now needed to realise this promise.